Infophilia, a Positive Psychology of information | June 16, 2025 | Vol. 3, Issue 35 | Knowledge Structures Toolbox | Bonus edition

✨Welcome to Infophilia, a weekly letter on how our love of information and connections can help the whole planet flourish.

Cite as: Coleman, Anita S. (2025, June 16). A civic infophile ahead of her time: Eliza Atkins Gleason (1909-2009). Infophilia, a positive psychology of information, 2 (35).

Dedication: To my mother, in honor of her birthday, with gratitude for nurturing my love of literature, African, Chinese, English, Indian, Russian, you name it!

Dear readers,

Over the weekend, after sharing Reimagining Innovation: From Bibliography to Civic Infophilia, I read an open letter from 400 academics including 31 Nobel Laureates, defending democracy. 3,000 citizens had also already signed on to support the cause!

Here are a few excerpts from the English version of A Century Later: A Renewed Open Letter Against the Return of Fascism:

On May 1, 1925, with Mussolini already in power, a group of Italian intellectuals publicly denounced Mussolini’s fascist regime in an open letter.

Today, a hundred years later, the threat of fascism is back — and so we must summon that courage and defy it again.

As in 1925, we scientists, philosophers, writers, artists and citizens of the world, have a responsibility to denounce and resist the resurgence of fascism in all its forms.

We call on all those who value democracy to act:

Uphold facts and evidence. Foster critical thinking and engage with your communities on these grounds. [emphasis mine]

Just ten days earlier, 2025 Holberg Laureate Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak — one of the few humanities scholars who have gained an international reputation for masterfully blending it with social justice — delivered a wide ranging lecture titled Imperatives to Re-imagine the Future. In her classic comparative literature style, she referenced philosophers, poets, and political theorists: Immanuel Kant (on the transcendental), Karl Marx (on imperatives, collective agency, and self-critique), Antonio Gramsci (the idea of e-laborare which means to work out system change), Rabindranath Tagore (on ethical imagination), and Mahasweta Devi for the subaltern (meaning the underserved voices we seldom hear). She also wove in:

Toni Morrison’s ‘invisible ink’ metaphor — the hidden stories in texts that the author leaves for the engaged, perceptive reader to find

Santee Dakota poet John Trudell’s reflective poem on natural rights and the intrinsic value of all living beings:

‘We must go/ beyond the arrogance/ of human rights./ We must go/ beyond the ignorance/ of civil rights./ We must step/ into the reality/ of natural rights./ Because all of/ the natural world/ has a right to existence/ and we are only/ a small part of it./ There can be/ no trade off.

Sundari, a poor woman in India, one of the teachers Spivak is teaching and learning from in Bengali, in a discussion of the “European antiquity’s imagination of the music of the spheres” is intrigued by the idea of an ocean floor in a sphere, and with the idea of fire there as well and asks "why, if the earth floated in water, there was such water shortage?”

Spivak suggests that the humanities can bring about systemic change by promoting a deep, global transformation in knowledge:

Natural violence has created an imperative to develop a planetary view of the future.... And the task of the humanities is to re-arrange desires, so that we learn to want differently, rather than think smart capital to supplement degrowth. (page 2)

She insists, there is no hope of a just society if every generation is not persistently weaned from the basic human affects of greed, fear, and violence and this has to cut across the race-class-gender apartheid. Unless there is persistent, sustained, and worldwide epistemic change, democracy and ethics cannot be desired. Knowledge will continue to be managed for greed, fear, and violence.

She closes with a warning:

democracy as persistent revolution, may well be over as mere human greed unleashes a wounded planetarity. Think of the implications of this, please, as I thank you and sit down. (page 13)

The bottom line: Teaching people to re-arrange their desires and to read beyond the disciplines is the “(im)possible task of the humanities.” (page 9)

Both of these serve as a perfect segue to keep my promise of also providing real life examples of infophilia research concepts and tools whenever possible through the Knowledge Structures Toolbox.

Therefore, here’s your next mission, should you choose to accept:

Defend democracy by adding your name to A Century Later: A Renewed Open Letter Against the Return of Fascism.

Take time to revel in the connections you discover reading about Eliza Atkins Gleason, an African American librarian and educator who was also a civic infophile. (Not a label she used, but my creative interpretation grounded in historical scholarship.)

By analyzing Dr. Gleason’s work and sharing it here, I’m doing at least two things: 1) providing another real life case of infophilia (our first was the Library of Congress dismissal of Dr. Hayden and Shira Perlmutter); 2) practicing my own civic infophilia skills by writing memorials for the Librarians We Have Lost: ALA Sesquicentennial Memories, 1976-2026 campaign.

Stay curious. Stay connected.

Anita

A Civic Infophile Ahead of Her Time:

Eliza Atkins Gleason (1909-2009)

A centenarian librarian whose life mapped the public good across generations, geographies, and global visions.

At a Glance: Dr. Eliza Atkins Gleason

Quick Facts

Born: 1909, Winston-Salem, NC.

Groundbreaking Achievement: First African American to earn a PhD in Library Science (1940).

Major Impact: Founded Atlanta University's Library School, training 90% of African American librarians until 1986.

Family Legacy: Daughter of Simon Green Atkins founder of Winston-Salem State University.

Breaking Barriers: First African American librarian on American Library Association's national council (1942-1946).

Personal: Married to Dr. Maurice Gleason for 61 years; mother to Dr. Joy Gleason Carew, who became the resident linguist (Russian) and Professor of Pan-African Studies at the University of Louisville (retired in 2020). Grandmother to Shantoba Eliza Kathleen Carew.

Intellectual connection: Carleton B. Joeckel (her dissertation advisor at the University of Chicago)

Died: 2009, on her 100th birthday, December 15.

Why Her Story Matters Today:

Today, we take the principle of universal information access for all as a basic human right. We often assume that’s what librarians have always believed and practiced. But it wasn’t always so. Many people have helped us get here, but now, through the lens of adaptive infophilia theory, (and specifically civic infophilia) I present the African American woman librarian and educator, Dr. Eliza Atkins Gleason. At a time when many African Americans were denied library services due to segregation, she studied the problem both legally and empirically. Her landmark study, The Southern Negro and the Public Library, exposed the gap between the professional rhetoric of “free libraries for all” and the reality of systemic exclusion. She argued for a single, integrated library system serving everyone equally. She built institutions and trained professionals dedicated to serving the "common good" embodied by public libraries. Her life is a testament to how one person's dedication to education and truth can reshape entire systems. It’s a lesson that is urgently needed as professions, institutions, and the public face contemporary challenges around access, censorship, misinformation, and the ongoing risks to collective memory.

1. A Daughter of an African American Educational Legacy Par Excellence

Eliza was born in 1909 in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, the youngest of nine children in a family deeply committed to education. Her father, Simon Green Atkins, was the founder of Slater Industrial Academy in 1892, now Winston-Salem State University (WSSU). He believed that “Education is primarily an effort to realize in man his possibilities as a thinking and feeling being.” Her mother, Oleona Pegram Atkins, was a teacher, a leader in her own right, and honored today as "WSSU’s First Lady.” Eliza inherited an ethic of "bibliography as biography" — a belief in books as tools of selfhood and service.

2. An Educational Journey Across the Nation: Navigating Historical Silences

Eliza's educational journey stretched across the nation from the American South to the Midwest to the West. She earned her A.B. from Fisk University, Nashville, Tennessee, in 1930, and her B.S. in Library Science from the University of Illinois in 1931. Her first library position as Asst. Librarian was that same summer at Louisville Municipal College (LMC) for Negroes. (LMC was a distinct municipal institution created during segregation, and under the administration of the University of Louisville; it closed in 1951 following desegregation of the University.) She became Head Librarian in 1932 and taught the only library classes available for African Americans in Kentucky between 1932–1951.

She left Kentucky in 1935 to pursue her M.A. in Library Science at the University of California, Berkeley, then returned to her A.B. alma mater Fisk University in 1936 as librarian, later becoming Head the Reference Department. In 1937, she moved to Chicago and earned her PhD in Library Science from the University of Chicago in 1940, becoming the first African American to do so. Her dissertation, published as a book in 1941, remains a landmark study of public library services (or not!!) to African Americans.

Dr. Gleason's intellectual journey was a civic pilgrimage, moving through segregated and elite institutions alike with one goal: to democratize access to knowledge. Analyzing Gleason’s landmark study, Cheryl Knott concludes in Not free, not for all: Public libraries in the Age of Jim Crow (2016):

"Gleason's book documented for the first time the extent of the gap between white librarians' words and their deeds. It revealed the hypocrisy of an institution and a profession that provided access to collections and services as if access were a privilege for whites to bestow rather than a civil right in a democracy founded on the notion of intellectual freedom." (page 46)

3. An Info-Pragmatist

In her doctoral study, Dr. Gleason meticulously documented that approximately 6.9 million African Americans in the South lacked access to public library services, with nearly 2 million living in areas where libraries were available exclusively for whites. Rather than invoking intellectual freedom, Gleason strategically argued against the financial and operational inefficiencies of segregated libraries, recommending desegregation as a more cost-effective solution.

Her pragmatic approach reflected the broader intellectual trends of the 1930s, when efficiency became increasingly important in public services. Gleason understood the political landscape — ALA had provided financial support for her education, but the organization was still focused on book banning and had not yet found its footing on civil rights even though the first Library Bill of Rights had been adopted in June 1939.

4. Builder of Institutions, Nurturer of Movements

She developed a library department at Louisville Municipal College (LMC), the only one in Kentucky to provide library classes for African Americans. As the founding dean of the School of Library Service at Atlanta University (Clark Atlanta now) in 1941, Gleason created the infrastructure for African American librarianship in the U.S. that trained 90% of African American librarians by 1986.

Her institution-building was grounded in a fundamental understanding that library policy was public policy. Her dissertation, The Government and Administration of Public Library Service to Negroes in the South published as The Southern Negro and the Public Library, explicitly examined library governance within the broader context of governmental responsibility and public administration. She exposed how the rhetoric of "equal access" in public library policy was contradicted by the realities of segregation, demonstrating that library policy both reflected and reinforced broader public policy failures.

In 1942, she became the first African American librarian to serve on the national council of the ALA and served until 1946.

She left the Atlanta school to join her husband in Chicago and after stints at various colleges became an associate professor in library science at the south Chicago branch of the Illinois Teachers College in 1964.

5. Pan-African Cosmopolitan and ‘Common Good’ Cartographer

From the segregated South to the Great Lakes North, from Louisville to Atlanta to Chicago, Eliza's life embodied a kind of African American civic cosmopolitanism or Pan African American internationalism — a grounded yet borderless vision for justice rooted in her understanding of the common good. Her analysis of the legal basis of free libraries (as public libraries were called then, since they were supported by taxpayer funds and provided services without individual personal payment) is simply brilliant. W.E.B. Dubois saw Pan Africanism as a global anti-racism strategy and her daughter’s intellectual accomplishments exemplify this tradition.

6. Personal Life and Continuing Legacy

Eliza married Dr. Maurice Francis Gleason in 1937, and after World War II, joined him in Chicago in 1946. Their daughter, Joy, was born in 1947, and they were married 61 years before Maurice passed away in 1998. Two of Simon Green's expressions guided Eliza throughout her life: the motto still used by Winston-Salem State University, "Enter to learn, depart to serve," and a personal motto that spoke to her fortitude, "I can buy a pound at any price."

Their daughter, Joy Gleason Carew, Ph.D., became a Professor of Pan-African Studies at the University of Louisville and author of Blacks, Reds, and Russians: Sojourners in Search of the Soviet Promise. She married Jan Carew in 1975, a Guyanese writer who described his ancestral village as "a place of polyglot races" where he was blessed with "the bloods of the most persecuted peoples on earth." Joy retired from the University of Louisville in 2020 after 20 years of service.

7. An Infophile in Action

Gleason wasn’t content to sit in silence. She believed library policy was public policy. Her dissertation remains one of the earliest works to critique structural exclusion in America’s public libraries through data and evidence — the very heart of civic infophilia.

In 2010, the University of Louisville posthumously inducted her into the College of Arts and Sciences Hall of Honor. The Eliza Atkins Gleason Book Award is given in her honor by ALA (administered by the Library History Round Table) for the best book written in English in library history, including the history of libraries, librarianship, and book culture.

From Biography to Civic Infophilia

Dr. Gleason's life exemplifies what we’ve been exploring as civic infophilia — a love of information rooted in the democratic impulse to use knowledge not just to live well ourselves, but to help others, especially those who are underserved, flourish too. This goes beyond typical civic participation or engagement and embraces historical erasures, silences, and violences with truth and empathy.

Eliza Atkins Gleason embodied this impulse decades before we had a name for it. Her approach to information and institutions was characterized by three key principles:

A love of information for equity's sake: She understood that knowledge without access is powerless, and that information systems must actively serve the common good.

A belief in information institutions as moral institutions: Libraries, schools, and archives weren't neutral spaces to her, but tools for democracy that required intentional stewardship.

A commitment to transcending all borders: Whether racial, regional, or national, she saw artificial boundaries as obstacles to human flourishing.

A Message for Our Times: Citizens and Librarians, Archivists and Historians, Everyone in the Helping Professions

If you care about truth, if you worry about censorship, if you are experiencing burnout or overload and wondering whether libraries, archives, museums, and education in the arts and humanities still matter; if you're looking at the signs and promises of movements such as open access, open borders, open science, and open cultures, know this:

Eliza Atkins Gleason saw the cracks in our democracy and filled them with books, schools, ideas, and voices. She didn't wait for perfect systems — she built better ones. You can let her legacy be your call to action in this fragile time.

A Call to Action

Who are the librarians and library school teachers who have inspired you? Did any of them pass away during the ALA Sesquicentennial period from 1976 to 2026? I invite you to honor their memory by sharing their names, along with any personal memories or tributes you’d like to offer. Your reflections will help celebrate their contributions to the library community and beyond.

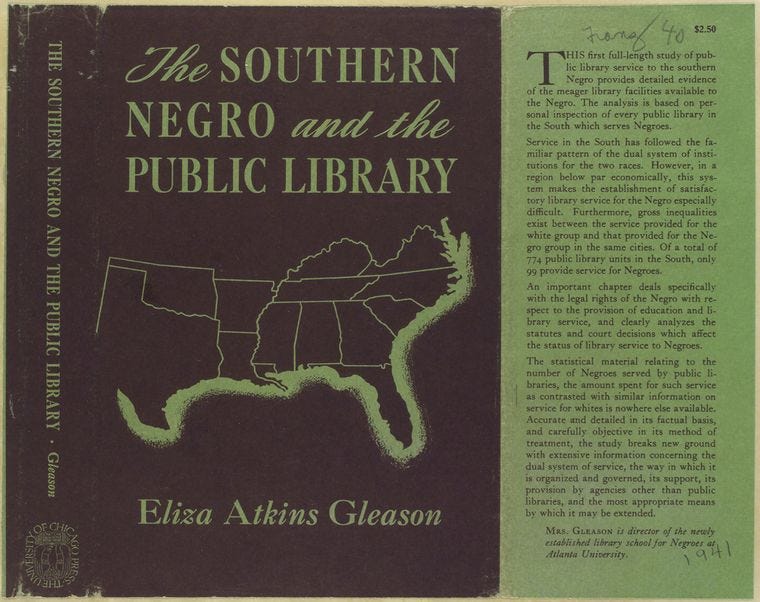

Featured image: The front cover of Eliza Atkins Gleason’s 1941 book published by the University of Chicago press The Southern Negro and the Public Library, highlights the 13 southern states that she investigated in her pioneering doctoral study on public library services for African Americans. The states are: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia and her dissertation title is The Government and Administration of Public Library Service to Negroes in the South.

References

American Libraries. "Dr. Eliza Valeria Atkins Gleason, 1909–2009." American Libraries 41, no. 3 (March 2010): 53.

Chicago Tribune. "Eliza Atkins Gleason Obituary." December 2009. https://chicagotribune.com/obituaries

Eliza Gleason Obituary. https://www.legacy.com/us/obituaries/louisville/name/eliza-gleason-obituary?id=8603463

General Research Division, The New York Public Library. "The southern Negro and the public library." The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1941. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47db-dbe0-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

Gleason, E. A. V. (1940). The government and administration of public library service to negroes in the south. A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the Graduate Library School in candidacy for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. University of Chicago. Chicago, Illinois. March 1940. 173 pages.

Jan Carew Official Website. "Biography." https://jancarew.com/

Librarians We Have Lost: ALA Sesquicentennial Memories, 1976 - 2026 campaign / project. Library History Round Table. https://lhrt.news/librarians-we-have-lost-sesquicentennial-memories-1976-2026/

Knott, Cheryl. "Changing Minds, Making a Difference: Eliza Atkins Gleason." UC Berkeley School of Information, 2019. https://www.ischool.berkeley.edu/news/2019/changing-minds-making-difference-eliza-atkins-gleason

Knott, Cheryl. Not free, not for all: Public libraries in the Age of Jim Crow. 2016.

Schlacter, Gail, A. and Thomison, Dennis. (1974). Library Science Dissertations, 1925 - 1972.

Simon Green Atkins and his family. Digital Forsyth. https://www.digitalforsyth.org/photos/stories/simon-green-atkins-and-his-family

University of Louisville. "Joy Gleason Carew Profile." https://louisville.edu/artsandsciences/news/perspectives/immigration/carew

University of Louisville Women's Center. "Obituary: Dr. Eliza Atkins Gleason." https://louisville.edu/womenscenter/signature-programs/faculty-staff/womens-empowerment-luncheon/past-luncheons/obituary-dr.-eliza-atkins-gleason

Notes

Spivak, G. (2025). Imperatives to re-imagine the future. 2025 Holberg Lecture. https://holbergprize.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2025/06/Spivak_Holberg_Lecture_040625.pdf

Spivak does not just theorize about social justice and the underprivileged. She works with and learns from these communities, especially in West Bengal, India. For over 30 years, she has taught and worked directly with marginalized people in rural areas, helping them get an education and feel like they have a voice. She wants to make these people feel like they are citizens, not just recipients of charity or policies. Her work shows that real change comes from talking and learning with those who are different, not just from academic theories. [emphasis mine]

Her Chicago advisor was Carleton Joeckel.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carleton_B._Joeckel