Infophilia, a positive psychology of information | January 4 2025 - Vol. 3, Issue 1

Welcome to Infophilia, a weekly newsletter exploring humanity’s enduring love for information. Here, I introduce a fresh, forward-thinking approach to information literacy—an essential skillset for navigating the overflow of information, the rise of generative Artificial Intelligence, the challenges of disinformation, and our rapidly evolving knowledge ecosystems.

As I look ahead to 2025, I’m deeply grateful for you, my readers. In this spirit of gratitude, I offer this essay as both a gift and a tribute to the foundational thinkers and ideas that have shaped—and continue to shape —the field of information literacy. Enjoy!

Information Literacy at 50: From Paul Zurkowski To Our AI Digital Age

Cite this as:

Coleman, Anita S. (2025, January 6). Information Literacy at 50: From Paul Zurkowski to our AI digital age. Infophilia, a positive psychology of information, 3 (1).

Infofools also tend to be siloed easily, either because their social media platforms do it to them or because they are overwhelmed with the voices out there and prefer to stay in their own info-family. Many voters from the past election tended to be ignorant about crucial information that could have swayed their vote. They had simply not encountered that information and seem to have had no interest in it either. This is a dangerous realm within which to live one's life. —William Badke (2024, December 28)

William Badke's observation about infofools on my recent Information Culture Wars essay highlights a timeless truth: information literacy matters more than ever now in the age of generative artificial intelligence, viral misinformation, overload, and knowledge transformation. Fifty years ago, in a report published November 1974, the American attorney Paul Zurkowski introduced the concept of information literacy to the world, envisioning citizens as active information users, not passive consumers.[1] Today, on its fiftieth anniversary as we navigate AI-generated content, algorithmic feeds, and polarized digital spaces, Zurkowski’s vision deserves fresh attention.

Bridges inspire me and the photo of the Natcher Bridge, a stunning cable-stayed structure linking Kentucky and Indiana that we traveled on recently, exemplifies the importance of investing in quality infrastructure. Just as a well-designed bridge ensures safe and efficient passage, investing in quality information enables informed decision-making and the building of a sustainable knowledge society. Information, like a bridge, comes with costs—time, effort, and resources. Healthy infophiles recognize these costs and prioritize reliable sources, while infofools rely on shortcuts, risking the collapse of their knowledge foundation. Both bridge-building and information literacy require foresight, investment, and a commitment to durability.

Zurkowski’s Universal Information Literacy (for all citizens)

…the top priority of the National Commission on Libraries and Information Science should be directed toward establishing a major national program to achieve universal information literacy by 1984. Zurkowski (1974)

Universal information literacy was the ambitious goal Zurkowski suggested in his 30 page report for the national program for library and information services. Last summer, at the American Library Association conference in San Diego, which I attended, the federal agency, Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS), unveiled informationliteracy.gov—a significant milestone in this ongoing journey.[2] The website serves as a resource for library and museum professionals, integrating multiple literacies: information, financial, health, digital, and science literacy.

However, librarians, journalists, and educators have long been at the forefront of efforts to teach and enhance information literacy, encompassing media, civics, and digital literacy. While strides have been made in fostering critical thinking and an “informed citizenry,” there remains room for improvement. In February 2024, Pew Research reported alarming levels of support for authoritarianism in middle income countries —85% in India and 71% in Mexico. By comparison, the United States and Canada reported lower support at 32% and 27%, respectively, with Sweden at just 8%. These figures highlight the urgent need for universal and robust information literacy to counter misinformation and foster democratic resilience in our interconnected world.

Zurkowski directly tied information literacy to the private sector’s ability to create wealth through a spectrum of information products, services, and systems—including information generation, publishing, technological applications, with freedom of expression as the basis for it all and the cornerstone of a thriving democracy.

Zurkowski’s Information Literates and Illiterates

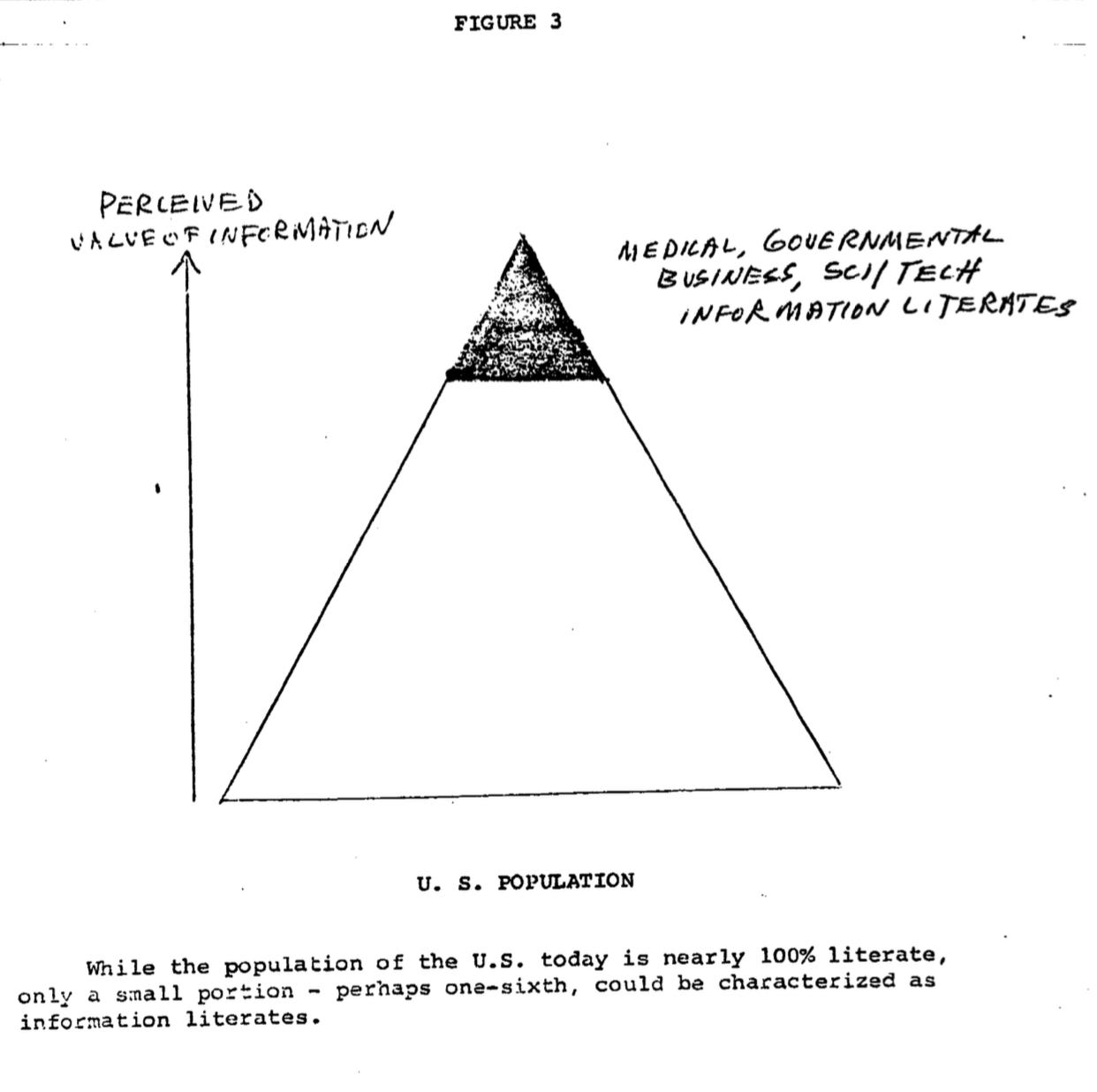

In setting out his call for universal information literacy, Zurkowski divided people in the USA then into two groups: information literates and information illiterates.

People trained in the application of information resources to their work can be called information literates. They have mastered techniques and skills for utilizing the wide range of information tools as well as primary sources in molding information solutions to their problems.

The individuals in the remaining portion of the population, while literate in every sense that they can read and write, do not have a measure value of information, do not have an ability to mold information to their needs, and realistically must be considered illiterates.

Zurkowski was writing in the 1970s, at a pivotal moment in the information age, when digital technology began to transform daily life, marking the true dawn of the Information Age. Even then, he recognized that information is not knowledge unless it is “molded” and that it’s “measured value” remains unknown to those who are information illiterate. By the 1990s, with the advent of the World Wide Web, the Information Age (i.e. the information economy) reached another critical stage in its evolution. Over the past 30 years of the WWW, we’ve witnessed the rise of digital natives and gained new knowledge about digital information use and users from different disciplines, progressing now into the age of AI.

In previous essays, I’ve explored frameworks like the ACRL, Information neighborhoods, UNESCO’s Media and Information Literacy, and ISTE’s standards for information literacy, media literacy and digital citizenship. I’ve also highlighted how the field has become a truly global discipline with its own conferences (e.g. European Conference on Information Literacy), and dedicated journals. Many countries and languages have developed their own terms for information literacy—for example in Tamil, a south Indian language spoken in the state of Tamil Nadu, information literacy is called தகவல் அறிதிறன் (Thagaval Arithiran).

Given all this education and exposure to digital information, people are no longer just information literates or illiterates—information literacy now exists on a spectrum. This is where my concept of infophilic information styles comes in, ranging from healthy infophiles to malaadaptive infofools, with in-between categories such as infopragmatists, infovores, infoseekers, and infocurious.

Despite the advances in education and understanding, the economics of information remain a challenge. Healthy infophiles invest time and resources in high-quality information, while infofools fall prey to low-cost or misleading content. Bridging these economic gaps is essential for building a more equitable and knowledgeable society.

Digital Information Economics: The True Cost of "Free"

The creation of a resource people can draw on, is a most capital intensive activity… Zurkowski, 1974

Zurkowski's insight about the economics of information proves prophetic in today's digital landscape. He argued that information's value as a service and product shouldn't be overlooked. Information is a valuable resource whose worth can be assessed based on its utility or relevance to specific decisions, actions, or processes. This is a principle that’s evident in debates over paywalls, digital subscriptions, open access, and content monetization.

Consider our contemporary realities:

Premium outlets (e.g. NY Times, Washington Post, LA Times) and aggregator sites (e.g. Apple News) maintain quality through subscription models

"Free" social media platforms extract costs through privacy compromises and data harvesting

Substack's revealing statistic: 95% free readers, challenging the platform's aspiration as "the home of great culture," independent journalism, and a “new economic engine”

AI-generated content, synthetic information, flooding digital spaces, is making human curation (which includes authoring, editing, fact-checking) more valuable

A seismic shift underway in academic publishing from paywalled content to open access is complicating the library's role (e.g. calls for open investing), as well as the nature of open knowledge and the public domain [3]

New online genres are emerging at the intersection of the Readers Service Environment and the Information Service Environment, blending traditional print formats with digital aesthetics and interactive engagement—an evolution that comes with real costs for creators and publishers.

Before the Information Age, the relationship between libraries and publishing was mutually beneficial, primarily existing within a Reader Service Environment, where the book or journal was the self-contained economic unit. In contrast, in the Information Age, we now operate within an Information Service Environment, where the foundation is a system based on freedom of expression and copyright. Books and articles can be photocopied, digitized, and a wide variety of derivative products for revenue can be generated. Similarly, information—such as public domain materials—can be molded, with revenue potential. For instance, Zurkowski notes the rise of micro-publishing and says it should rightly be called micro-republishing.

Information is money is power. (Zurkowski in Badke, 2010)

In this new environment, Zurkowski astutely observed that libraries and the information industry (both non-profit libraries and the for-profit publishing and information industry sectors) are “seeking to serve the same users.” This creates an uneven playing field, as libraries are tax-exempt while for-profit companies are not. His argument for a private information sector is compelling. However, the key point I want to highlight here is his analysis of the economics of information. Producing and distributing quality information requires a financial investment, and healthy infophilic information styles recognize this reality, understanding the value of quality information and being willing to pay for it.

For Zurkowski, simply giving information away, causes deterioration of its value and in the end, results in a degeneration of quality… To the extent that we undermine the business value of the most important information in our society, we end up with shabby information…Much as I champion open access and the Creative Commons licenses, I resonate with the simple fact that someone has to pay for things… Badke, 2010.

Your 2025 Information Literacy Checkup

As we enter 2025, I encourage you to conduct an Infophilic Information Styles review—a structured self-assessment of your digital information habits particularly in relation to how you gather, use, and consume news. This review should focused on sources you rely on, the formats you prefer, the balance between information consumed and used, and the associated $ costs. (Watch for an online poll in next week’s post to help guide this process.)

This reflection comes at a timely moment:

Platform algorithms increasingly determine the information we encounter (i.e information exposure)

AI tools are transforming content creation, consumption, and use

Quality journalism is facing critical sustainability challenges

Digital citizenship requires active, informed participation

Democratic institutions, such as free press and an independent judiciary, are at a defining crossroads[4]

Building a Sustainable Information Future / The Knowledge Society

In essence then, a knowledge producing society is a powerful and free society whose information generates wealth for the nation as a whole. —Badke

The disparity between free and paid readership, as well as information use versus consumption, reflects not only economic choices, but deeper misconceptions about the value of information. When we expect all information to be free, we risk:

Undermining independent journalism

Reducing content quality

Creating unsustainable creator economics

Fostering an environment where misinformation thrives

Just as a bridge requires careful planning and investment to ensure its durability, building a sustainable knowledge society demands thoughtful consideration of the costs and benefits of information. Information is not a free good—it comes with costs in terms of creation, maintenance, and distribution. We invest in this infrastructure when we pay taxes, support subscription-based services, and contribute to open knowledge platforms like Wikipedia. These are just a few of the ways we can support the system. By valuing information as a critical resource and recognizing that "free" access often hides hidden costs—such as ads, data harvesting, low content quality—we can collectively create a future where knowledge serves as a foundation for progress and informed decision-making.

This understanding has shifted my approach to sharing information. As an open access champion during my time as a faculty member, I once believed that scholarly information should be openly and freely available. However, as an independent scholar now, I’ve come to realize that giving away valuable intellectual work without compensation undermines and devalues the sustainability of quality knowledge production. When we support the infrastructure that sustains quality information, we ensure its value is recognized and its availability is sustained for all.

Next Steps

As we mark fifty years of information literacy, I want to honor Zurkowski's pioneering vision and its evolution through scholars like the Australian Christine Bruce (Information Literacy Blueprint (1994) whose work I’ll discuss next, mapping her Seven Faces of Information Literacy to my concept of adaptive infophilia and personal information styles). Their insights provide valuable guidance for navigating today's challenges. In a world shaped by technology, economics, and human behavior, we're all on a journey from infofools to infophiles.

Key Takeaways

The 50-year journey of information literacy reveals critical lessons:

The Silos of Ignorance:

Information isolation occurs through both external forces (algorithmic filtering) and internal choices (like information avoidance, knowledge resistance). Recent elections around the world —particularly in the super election year 2024 —demonstrate how citizens can remain unaware of crucial information simply because they never encounter it or choose not to seek it out.

Economic Realities of Quality Information:

Premium news outlets maintain quality through subscription models.

"Free" information often comes with hidden costs: low quality, misinformation, and privacy compromises.

The widespread availability of free, low-quality content creates an information environment dominated by noise rather than meaningful signal.

We must become better educated about the economics of information

Digital Citizenship Responsibilities:

Information literacy for all citizens is more needed than ever.

Active information seeking across diverse sources is necessary.

Critical evaluation of both free and paid information sources is key.

We must recognize that quality information has inherent value and is worth investing in.

Media Ecosystem Awareness:

Understanding how different funding models affect content quality.

Recognizing how platform algorithms can create information bubbles.

Appreciating the relationship between information access and democratic participation.

Personal Information Habits:

Regular exposure to diverse viewpoints is essential.

Willingness to invest in quality information sources is crucial.

Active resistance to algorithmic isolation is much needed.

Developing critical evaluation skills is fundamental.

Information literacy is a fundamental requirement for meaningful participation in modern democracy and global citizenship.

Notes

Fun Fact: Zurkowski was called the Johnny Appleseed of Information.

Some of Zurkowski's Accomplishments / Legacy

1964: Worked with Congressman Kastenmeir on what later would become the Copyright Act, responsible for the Fair Use doctrine

1968: Drafted original charter for the Information Industry Association (IIA)

1969-1989: Founding President of the Information Industry Association, promoting the role of information in national policy and value in business sector.

1974: Coined the phrase "Information Literacy" in his NCLIS report - pioneered the concept in a workforce context, advocated for its integration into educational systems, and its importance for modern society —basically setting the agenda for future developments in the field. (Lee Burchinal helped the focus to specific skills)

By 1989: Grew IIA from 9-12 founding companies to over 700 focused businesses.

In 2003, UNESCO declared information literacy a "human right of lifelong learning.” On Oct. 1, 2009, President Obama proclaimed October as National Information Literacy Month. In 2015, the Association of College and Research Libraries developed a Framework for Information Literacy in Higher Education, further refining the concept. In 2024, IMLS unveiled informationliteracy.gov

Zurkowski didn’t actually develop a comprehensive economics of information. He laid the groundwork for understanding information as an economic resource (e.g. first copy costs, information equivalents.) and information literacy as a key skill that could unlock economic value in the information economy, that was just emerging. He saw information literacy as a way to help economic and international growth.

Badke, W. (2010). Foundations of information literacy: Learning from Paul Zurkowski. Online Magazine 34 (1): 48-50. https://www.proquest.com/docview/199913289

Burchinal, L. G. (1976, Sept. 24). The communications revolution: America’s third century challenge. In The future of organizing knowledge: Papers presented at the Texas A & M University Library’s Centennial Academic Assembly. College Station, TX: Texas A & M University Library.

IMLS Debuts New Federal Resource, InformationLiteracy.gov, at American Library Association Conference (June 2024). https://www.imls.gov/news/imls-debuts-new-federal-resource-informationliteracygov-american-library-association

Information Literacy. (n.d.). Universal Literacies Association. Retrieved December 31, 2024, from https://uilaz.info/

Landøy, A., Popa, D., & Repanovici, A. (2020). Collaboration in Designing a Pedagogical Approach in Information Literacy. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-34258-6

Polger, M. A. (n.d.). CSI Library: Information Literacy: Definition and Importance: President Obama’s proclamation - National Information Literacy month. Retrieved December 31, 2024, from https://library.csi.cuny.edu/c.php?g=1358097&p=10028395

William H. Natcher Bridge. https://www.wsp.com/en-us/projects/william-h-natcher-bridge

Paul Zurkowski

Paul G. Zurkowski died on Jan 30, 2022. Legacy.com https://www.legacy.com/us/obituaries/washingtonpost/name/paul-zurkowski-obituary?id=33132092

Funeral for Paul George Zurkowski -- founder of the Information Literacy Movement. InfoLit Group (UK) (2022). https://infolit.org.uk/passing-of-paul-george-zurkowski/

Zurkowski, Paul G. (1974) The Information Service Environment Relationships and Priorities. Related Paper No. 5. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED100391.pdf

Zurkowski, Paul G. (1979, Sept. 15). Information and the Economy. Library Journal, 104: pp. 1800-1807.

Zurkowski, Paul G. (1981, July). The Library Context and the Information Context: Bridging the theoretical gap. Library Journal, 106: pp 1381-1384.

Zurkowski, P. G. (2013). Information Literacy Is Dead... Long Live Information Literacy. Communications in Computer and Information Science, 397 CCIS, 1–10. Scopus. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-03919-0_1

Cacchione, P. Z., & Zurkowski, P. G. (2014). Nurse Scientists’ Information Literacy Is Supported by Librarians. Clinical Nursing Research, 23(1), 3–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/1054773813520267

Webber, S. (2013). Paul Zurkowski @ #ecil2013. Information Literacy Blog. https://information-literacy.blogspot.com/2013/10/paul-zurkowski-ecil2013.html

Zurkowski, P. G. (1977). Approaching Economic Environment. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, PC-20(2), 54–55. Scopus. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPC.1977.6592322

[1] Zurkowski, Paul G. (1974). The Information Service Environment Relationships and Priorities. Related Paper No. 5. A report to the National Commission on Library and Information Science (NCLIS), the predecessor to the current US federal Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS). Retrieved Dec. 28, 2024 from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED100391. The report suggested that the goal of the government program for

[2] Homepage | Information Literacy. informationliteracy.gov. The Taskforce behind this initiative included representatives from the major governmental agencies with “comprehensive and robust information literacy programs and/or grants available to communities across the country.” Remarkably, this also brings together a public-private-governmental leadership for diverse literacies (e.g. health literacy, financial, media, citizenship, and other literacy) along with information literacy. See also the Universal Literacies Association.

[3] Verbeke and Brundy. (2024). How Open Investing Will Transform Library Collections. https://katinamagazine.org/content/article/main-section/2024/how-open-investing-will-transform-library-collections presents several fallacious arguments. Open access models requiring libraries to fund publishers for openness - promoted as “library open investing” - are framed as ethical alternatives to paywalls, oversimplifying the nuanced role of paywalled systems in sustaining high-quality scholarly communication. They undervalue the unpaid labor of academics in peer review and editing, undermine the library’s role as a knowledge storehouse, and muddy the public domain. By perpetuating the disconnect between valuing quality information and supporting its production, these models shift the library's focus from holistic stewardship of information to a narrower, transactional role, compromising its mission and the sustainability of scholarly communication.

[4] https://www.reuters.com/world/democracy-heads-into-2025-bloodied-unbowed-2024-12-24/

Universal Information Literacies, from the Universal Literacies Association website:

Anton Zeilinger: "It is operationally impossible to separate Reality and Information." Information Literacy becomes the umbrella literacy encompassing:

Reading, writing and math (foundational) literacy

Computer literacy

Media literacy

Digital literacy

Tech literacy

Financial literacy

Transliteracy

Metaliteracy

And many others

My Related Essays on Infophilic Information Styles

Paul Zurkowski was very influential in early days of NCLIS. I have added a citation to his 1974 paper to the NCLIS Wikipedia page. Thank you for tracing the path. I also suggest looking at the National Advisory Commission on Libraries (1966 ) precursor to NCLIS as the membership is telling.