Infophilia, a Positive Psychology of information | May 3, 2025 | Vol. 3, Issue 21

✨Welcome to Infophilia, a weekly letter exploring how our love of information and connections can help us all thrive, individually and collectively.

Update: If you appreciated my bonus edition on Vibe Coding Explained: AI code generation, hyperscale data centers, and the need for human oversight, and want something more technical and focused purely on vibe coding, I encourage you to explore these two essays I came across after publishing my own:

1) Panda, Dixyantar. (April 25, 2025). The Vibe Coding Conundrum: Enslave AI or Cultivate Human Understanding, Stackgazer.

2) Neubig, Graham. (May 1, 2025). Vibe Coding Higher Quality Code, All Hands AI.

These essays also helped me crystallize a broader question I’ve been exploring: How do we, as people who love information and connection, build literacy around the infrastructures shaping embodied digital life?

In a world increasingly shaped by systems we can’t always see, for example, such as sensors in our homes, data in our bodies, networks behind our screens, it’s easy to feel like we’re always playing catch-up. The many ways our physical lives are increasingly shaped by digital systems can also be stressful. But instead of leaning into alarm or FOMO, I offer you an invitation: How might we build infrastructure literacy rooted in kind curiosity, not panic? What does it look like to understand the systems shaping our embodied digital lives, not to master them, but to relate to them more consciously?

These questions led to today’s essay. Enjoy!

Infrastructure Literacy

Understanding the Internet of Bodies

Cite as: Coleman, Anita S. (2025, May 3). Infrastructure literacy: understanding the Internet of Bodies. Infophilia, a positive psychology of information, 3 (21).

May is Mental Health Awareness Month in North America and our understanding of wellness today is increasingly intertwined with information technology. Beyond the apps that track our exercises, moods, and meditation minutes, we're witnessing the emergence of a more profound shift: the digitization of our bodily experiences and behaviors. This transformation raises critical questions about the intersection of health, technology, and personal sovereignty.

Digital Behavioral Capture

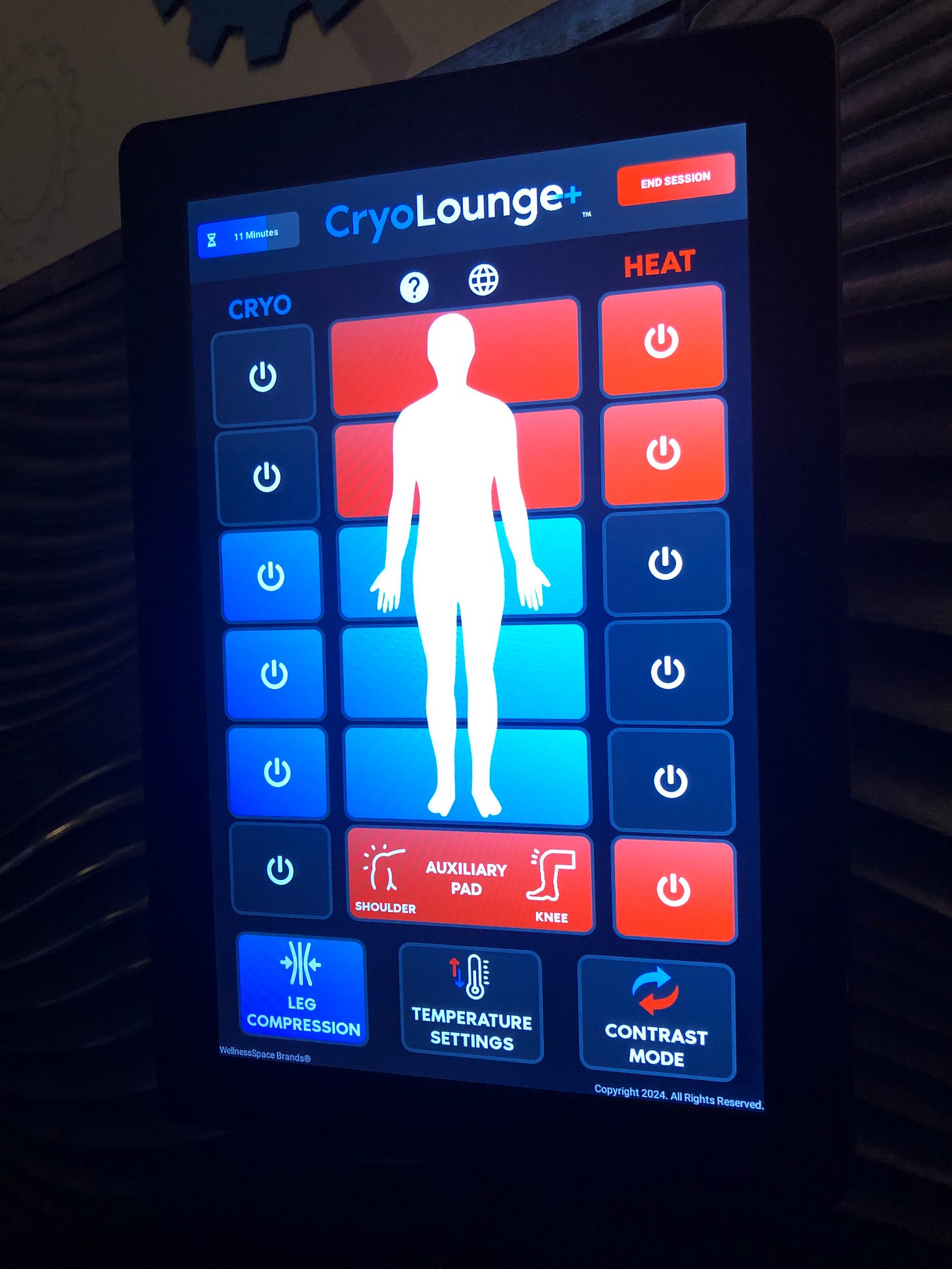

In the fall of 2023, Planet Fitness—the gym for the rest of us without beach bodies—began offering "recovery lounges" with cryo massage. Sit in a high-tech chair, get blasted with cold air, feel better fast. Simple, right?

Not quite.

What appears as a straightforward wellness service represents the leading edge of a much larger trend. Cryo massage is no longer just a perk—it's part of a broader shift where our bodies are becoming data points in a hyper-personalized feedback loop. Heart rate, circulation, inflammation response: all quietly monitored, analyzed, and increasingly owned by someone else. This is the Internet of Behavior (IoB), where behavior becomes biometric, and recovery becomes information. It's also the Internet of Bodies representing a direct extension of the Internet of Things to the human body. A continuous glucose monitor (CGM), for example, is considered an Internet of Bodies (IoB) device. Other Internet of Body devices like digital pills, pacemakers, insulin pumps, and smart health monitors collect and transmit real-time physiological data (e.g., heart rate, glucose levels) directly to healthcare providers, enabling early detection of health issues and timely or remote proactive interventions.

The Infrastructure of Behavior

Imagine this near-future scenario: Your Oura ring doesn't just track your sleep—it subtly nudges you toward bed by dimming your smart lights when your cortisol patterns suggest fatigue. Your Apple Watch doesn't just monitor your heart rate—it sends the patterns to your insurance company, which adjusts your premium in real-time based on your stress response during your morning commute. Your local gym's smart equipment doesn't just count your reps—it builds a proprietary profile of your strength-to-fatigue ratio that you can't access but third-party advertisers somehow can.

As of today, none of these specific scenarios are reality—yet. But they could easily become so as trends in software integration, personalized pricing of wearable data, and dynamic pricing converge, fueled by AI.

When Professor Göte Nyman conceived of the IoB in 2012, he imagined a system where each human behavioral pattern could be assigned a digital address, like IP addresses for actions rather than devices. What he couldn't have anticipated was how quickly this infrastructure would become the backbone of a new socioeconomic order—one where our most intimate bodily functions become tradable assets. The Internet of Bodies, a term coined in 2016 and formalized by Professor Andrea M. Matwyshyn, represents a direct extension of the Internet of Things (IoT) to the human body. The Internet of Behavior builds upon both IoT and Internet of Bodies by analyzing the behavioral data these networks produce to influence or predict human actions.

The architectural design is brilliant in its subtlety: we willingly strap sensors to our wrists, install listening devices in our bedrooms, and submit our DNA to corporate databases. We've become eager participants in our own behavioral capture, all for the promised convenience of a "quantified self" or a greater understanding of ourselves.

From Individual Bodies to Collective Knowledge: The Data Extraction Economy

Infrastructure should exist to serve people first, but recent trends suggest a troubling inversion of this principle.

Last month, April 2025, Wikimedia sounded an alarm: their infrastructure was being overwhelmed by automated bots, most of them scraping content to train AI systems. Traffic patterns revealed a disturbing shift—machines were consuming knowledge faster than humans could produce it. The free exchange of information, once Wikimedia's guiding principle, had become a one-way extraction highway.

This isn't just a technical problem of bandwidth costs or server load. It’s existential. When bots outpace humans in consuming and remixing knowledge, we risk eroding the communities these platforms were built to serve. The value created by millions of volunteer contributors is being siphoned into proprietary AI systems with no attribution, no reciprocity, and no transparency.

Wikimedia's response is instructive: they began redirecting automated reuse into curated channels—APIs with authentication requirements, documented access pathways, attribution protocols. They established aggressive benchmarks: identifying users behind 50% of automated traffic, reducing scraping bandwidth by 30%, publishing attribution guidelines specifically for large language models. They reasserted that their infrastructure exists to serve people first.

Libraries face similar challenges as AI systems scrape their catalogs and repositories. The traffic patterns at university libraries show sudden spikes when new AI models are in training, crawlers methodically consuming every metadata record, bandwidth costs creeping upward while actual human researchers experience slower response times. The solution isn't to lock everything down but to create openness with intention, i.e. designing systems that serve people first, not machines.

When Bodies Become Data: Security and Sovereignty Concerns

Enter post-quantum cryptography (PQC)—the emerging frontier of digital security. With quantum computers on the horizon, today's encryption may soon be obsolete. PQC aims to secure everything from state secrets to... your cryo session? Absolutely. Because if biometric data is the new currency of personalized health and warfare alike, then it's a national security asset—and a privacy landmine.

The IoB (behavior and bodies) represents a fundamental shift in how capitalism extracts value—not just from your labor or your purchases, but from the very patterns of your existence, your body. Your circadian rhythm, your walking gait, your iris movements while reading this text: all transformed into behavioral surplus for prediction markets you'll never directly benefit from.

The risks aren't theoretical. Although there is no publicly documented data breach of Internet of Bodies powered systems such as those that collect and process biometric or physiological data from wearables, medical implants, or advanced student monitoring technology, there have been breaches of genetic data. In the 2023 23andMe data breach hackers accessed the genetic information and ancestry details of approximately 6.9 million users through credential stuffing attacks. This breach represents a particularly severe case of vulnerability, where not just our behavioral patterns but our very genetic code becomes a target. To be clear, this is typically not described as an "Internet of Bodies" (IoB) incident in official reporting, but it does highlight the risks of digitized, deeply personal biological data. Unlike credit card numbers that can be changed or passwords that can be reset, genetic data is permanently linked to identity and can reveal sensitive information about health predispositions, family relationships, and ethnic background. The compromised data later appeared for sale on dark web forums, sorted by ethnicity and health conditions, demonstrating how our most intimate biological information can be commodified once digitized.

Compounding these concerns, 23andMe's March 2025 bankruptcy has created significant uncertainty about the ownership and future use of its customers' genetic data. While customers retain some rights, the company's privacy policy allows for the potential transfer of data in a sale, and the ultimate fate of that data will depend on legal interpretations, the terms of any sale, and evolving privacy laws. This situation highlights a critical vulnerability in our current data ecosystem: even when companies initially promise responsible stewardship of our most sensitive information, business failures can leave that data in limbo, potentially available to the highest bidder in bankruptcy proceedings.

On the beneficial side, continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) is a highly beneficial application of Internet of Bodies technologies. CGMs provide real-time, continuous data on glucose levels, enabling better diabetes management, reducing the risk of both high and low blood sugar events, and improving overall quality of life for people with diabetes. CGM devices allow for more precise treatment adjustments, fewer fingerstick tests, and earlier detection of dangerous trends, which can help prevent complications and is now considered standard of care for many people with type 1 and insulin-treated type 2 diabetes.

When our behavioral data—whether biometric, genetic, physiological personal health or intellectual—becomes vulnerable, so do we. And once that data is collected—by a fitness app, a library catalog, or a smart chair—it lives somewhere, potentially vulnerable to future breaches if not protected by quantum-resilient systems. (Library catalogs, these days, typically do not retain permanent borrowing histories unless a patron opts in. Libby and similar apps do record ebook borrowing history by default, but users have the ability to clear or disable this history, meaning it is not necessarily kept forever.)

The Question of Ownership vs. Control

Do we "own" our behavioral (and other) data?

The legal frameworks around this question vary widely. Finland's MyData initiative gives individuals strong rights and control over their personal data, including behavioral metadata, and the ability to withdraw consent for its use at any time. However, it does not create a legal framework where individuals literally "own" their data in the property sense, but rather ensures control and agency over data use and sharing.

This distinction between ownership and control is crucial. In most jurisdictions, the data about you isn't legally "yours"—but your ability to control how it's used, who accesses it, and for what purposes may be protected through privacy regulations like GDPR in Europe or CCPA in California.

The question isn't simply "who owns you?" but rather "who controls the patterns that constitute your digital existence?"

The power dynamics are shifting beneath our feet. When Michel Foucault described biopower, he imagined institutional control over bodies through medical knowledge and population statistics. Today's biopower operates through predictive analytics and behavioral nudging—less visible but more pervasive. You're not being surveilled through a panopticon; you're being guided through a datascape or as Prof Matwyshyn puts it your body is being “platformized.”

True agency in this landscape requires not just privacy controls but infrastructure literacy: understanding how your behavioral (and other) data flows through systems, who profits from those flows, and what alternative architectures might look like. Different stakeholders have unique roles to play in this landscape:

Information professionals must develop and advocate for transparent data stewardship practices

Healthcare providers must navigate the tension between innovation and informed consent

Security experts need to understand how biometric flows intersect with cybersecurity risks

Content creators and platform developers must design with community values in mind

Individual users require both knowledge and tools to assert control

Here are some strategies for reclaiming your agency:

Demand Dynamic Consent

Traditional digital consent is binary and static—a one-time checkbox that grants perpetual access. Behavioral consent must be dynamic and contextual, allowing individuals to control not just what data is collected but what patterns can be inferred from it. Finland's MyData initiative demonstrates how individuals can maintain ongoing control over their data's use.Support Transparent Systems

We need to shift from algorithmic black boxes to algorithmic glass houses; this is a widely recognized principle in AI ethics and explainable AI and reflects a real trend. When Netflix recommends a show based on your viewing patterns, you should be able to ask "why this recommendation?" and receive an explanation that you understand; right now Netflix gives only high level explanations not individual cases. Georgia Tech's "Transparent Machine Learning" project demonstrates how behavioral systems can expose their own decision-making processes without sacrificing effectiveness.Create Infrastructure with Intention

Whether you're a library providing catalog access, a Substack writer publishing content, or a fitness platform collecting biometric data, design your infrastructure with clear purpose. Create documented access points like APIs rather than allowing indiscriminate scraping. Monitor traffic patterns to identify high-frequency crawlers and implement rate limits that protect human access. Require attribution so that when AI systems incorporate your content or data, the sources are acknowledged. (APIs and rate limits may not be realistic advice for all Substack writers but do make copyright clear and include cite this as information; if you notice scraping or abuse, notify Substack support so they can mitigate it.)Build Counter-Technologies

Privacy enhancing browsers and extensions (e.g. Brave) and the Data Detox methodology developed by the Tactical Technology Collective (Tactical Tech), a Berlin-based non-profit, in collaboration with the Mozilla Foundation, can systematically reduce your behavioral footprint across platforms. The Data Detox Kit provides practical steps for you to reduce your digital footprint and regain control over your data, such as clearing location data, tidying up apps, and untagging yourself from photos and is widely used in privacy education.Advocate for Collective Governance

The most promising approaches combine technical innovation with social reimagining. Barcelona's DECODE project creates neighborhood-level data cooperatives where communities collectively govern their behavioral data. Members decide which patterns can be used for public benefit (like improving transit schedules based on movement data) while protecting sensitive behavioral information.

Getting Started Today

If these feel overwhelming, simple first steps for digital privacy and autonomy include:

Use a browser like Brave on all your devices.

Use DuckDuckGo.com / duckduckgo.ai to search and chat if you must chat with an AI chatbot.

Avoid downloading apps as much as possible.

Review privacy settings on your existing health and fitness apps, enabling the strongest protections available.

Try a "data detox" by using the Mozilla Foundation's free guide to reduce your digital footprint.

Before signing up for a new wellness service that collects biometric data, read the privacy policy with specific attention to data sharing, selling, and retention policies.

Support organizations advocating for stronger accountability, data protection laws, and ethical AI development. Support or call for regulations that clarify who is responsible if an IoB device causes harm or is misused.

Stay informed about device vulnerabilities: Wearables and medical IoT devices are susceptible to hacking, so keep up with security updates and patches for any connected health devices you use.

Be wary of workplace or institutional mandates: Some employers or organizations may require IoB devices for monitoring; consider the implications for autonomy and privacy before consenting.

Watch for bias and discrimination: Data from IoB devices can introduce or reinforce biases, so be alert to how your data might be used in ways that could affect access to insurance, employment, or services.

Monitor for gray-market risks: As regulations tighten, unauthorized or unregulated IoB devices may appear on the market, often lacking proper safety or privacy protections.

Engage in public dialogue: Participate in discussions about the ethical and legal frameworks needed to govern IoB technologies, ensuring your voice and concerns are heard as policies develop

From Extraction to Flourishing

The promise of the Internet of Behavior is real: Doctors can use behavioral data to detect early signs of injury or illness and deliver effective treatments. Information professionals can help design ethical health data systems. The military can apply these insights to optimize recovery and readiness. Everyday users can benefit from smarter self-care.

But without infrastructure literacy and intentional design, the risks are equally real: Health data leaks, surveillance wrapped in wellness, unregulated platforms collecting behavioral patterns that reveal more about you than your social media ever could.

The Internet of Behavior doesn't have to be a system of control; it can be a true system of care. It could be a platform for collective intelligence, for deeper self-understanding, for communities to solve shared problems. But achieving this vision requires more than technical fixes—it demands a fundamental rethinking of who behavioral data serves and who decides how it's used.

As you interact with behavioral systems today—whether checking your sleep score, reading a digital article whose engagement metrics are being tracked, or unlocking your phone with facial recognition—ask yourself: Who benefits from this pattern? Consider practicing dynamic consent by regularly reviewing and adjusting your privacy settings, rather than accepting the defaults and forgetting about them.

The metadata landscape is still being formed. We still have time to shape it. The question is whether we'll design it for extraction or for flourishing—whether we'll build a behavioral economy that commodifies human experience or one that amplifies human potential.

Cryo massage might cool your muscles—but don't let it freeze your awareness of who controls your body and behaviors.

Notes

Internet of Bodies appears to be the standard term used rather than Internet of Behavior. But both terms are sometimes used interchangeably!

Planet Fitness Privacy Policy. (January 2025). https://www.planetfitness.com/privacy-policy/your-privacy-rights | Planet Fitness Recovery Lounges feature regular massage chairs, hydro massage and cryo massage recliners. The CryoLounge chairs offer both cryotherapy (cold therapy) and thermotherapy (heat therapy), and can alternate between the two for "contrast therapy." Users sit or recline in a high-tech lounge chair that targets specific body areas with cold or heat, and the chairs also feature leg compression massage. The experience is designed to help reduce inflammation, relax muscles, and speed up post-workout recovery. Please note: The massage chairs in the Planet Fitness studios I visited don’t collect personalized biometric data.

The Internet of Behavior extends the Internet of Things by linking behavioral data to digital systems (through devices such as smartwatches, fitness watches, and cars) that can monitor, analyze, and influence actions. Although Prof,. Nyman conceived the Internet of Behavior in 2012 it didn’t gain popular currency until Gartner, in 2020, predicted that IoB would significantly influence people’s lives by 2025. Prof. Matwyshyn doesn’t cite Nyman (at least not that I could find) but her Internet of Bodies builds on it and raises key ethical concerns include privacy, security, autonomy, equity, surveillance, and the need for robust governance including self-governance.

The core idea behind the Internet of Behaviors (IoB) is to provide means to personally code, register, share, and address (individual or organizational) behaviors and to use pre-defined IP (v6) addresses to be used as individuals or any communities see as best. By IP a person can indicate his current intentions and behaviors. In doing this, it is not necessary to think about ‘addresses’ – it is possible to use seamless or ubiquitous future UIs of which various designs can be easily imagined. Thinking about the potential of the future technologies it is a fascinating challenge to design such interfaces for individuals, friends, families, couples, colleagues, and to trusted outsiders. What could a personal repertoire of IPs be like, and what can it offer? Göte Nyman. (October 2012). The psychology behind Internet of Behaviors. (Blog) https://gotepoem.wordpress.com/2012/10/

We are building an “Internet of Bodies”—a hybrid society where computer code and human corpora blend and where the human body is the new technology platform. In November 2017, the Federal Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first use of a “digital pill”3 that communicates from inside the patient’s stomach through sensors,4 a smartphone,5 and the Internet.6… This Article has introduced the ongoing progression of the Internet of Things into the Internet of Bodies—a network of human bodies whose confidentiality, integrity, and availability rely at least in part on the Internet and related technologies. Andrea Matwyshyn. (2019). The Internet of Bodies. William and Mary Law Review, 61, p. 77- 167. https://wmlawreview.org/sites/default/files/Matwyshyn-Internet%20of%20Bodies-Final.pdf

The Quantified Self. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quantified_self | The Quantified Self (QS) movement was founded in 2007 by Gary Wolf and Kevin Kelly of Wired Magazine

How crawlers impact the operations of the Wikimedia projects (originally published April 1) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:Wikipedia_Signpost/2025-04-09/Op-ed | See especially the section titled: Our content is free, our infrastructure is not: Establishing responsible use of infrastructure and their commitment to “knowledge as a service.”

Biometric data in consumer wellness tech is rarely confined to the user; it's often stored in cloud systems governed by opaque policies. For how to protect your data from ChatGPT and other AI chatbots see Mozilla's Privacy Not Included. https://www.mozillafoundation.org/en/privacynotincluded/

On predictive profiling and algorithmic decision-making, see: Kate Crawford, Atlas of AI: Power, Politics, and the Planetary Costs of Artificial Intelligence. (2021). Yale University Press. https://katecrawford.net/

Post-quantum cryptography aims to secure data against quantum decryption. See: NIST's Post-Quantum Cryptography Project — https://csrc.nist.gov/Projects/post-quantum-cryptography.

Michel Foucault’s idea of biopolitics frames how institutions manage populations by regulating bodies—see The Birth of Biopolitics (1979). Today’s wellness tech reflects a soft power version of this: optimization as governance.

Healthcare data breaches and cyberattacks in healthcare are widespread and growing. The HIPAA Journal. https://www.hipaajournal.com/healthcare-data-breach-statistics/ | https://spin.ai/blog/recent-healthcare-data-breaches-expose-growing-cybersecurity-risks/ | Seh, A. H., Zarour, M., Alenezi, M., Sarkar, A. K., Agrawal, A., Kumar, R., & Khan, R. A. (2020). Healthcare Data Breaches: Insights and Implications. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland), 8(2), 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8020133

23andMe data breach. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/23andMe_data_leak

23andMe filed for bankruptcy. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2025/03/24/nx-s1-5338622/23andme-bankruptcy-genetic-data-privacy

Steve Edelman, Wayman W. Cheatham, Anna Norton, Kelly L. Close; Patient Perspectives on the Benefits and Challenges of Diabetes and Digital Technology. Clin Diabetes 15 April 2024; 42 (2): 243–256. https://doi.org/10.2337/cd23-0003

Finland’s My Data initiative. https://mydatafi.wordpress.com/

GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) is the European Union’s data privacy law that gives EU citizens control over their personal data, requiring organizations to be transparent about how data is collected, used, and shared, and to obtain explicit consent for processing sensitive information. CCPA (California Consumer Privacy Act) is a California law granting residents rights over their personal information, including the right to know what data is collected, request deletion, opt out of sale or sharing, and be free from discrimination for exercising these rights. Both laws impose strict obligations on organizations handling personal data to protect individuals’ privacy.

Barcelona DECODE. Decentralised Citizens Owned Data Ecosystem was a high-profile European project, 2016 - 2020, piloted in Barcelona, focused on citizen data sovereignty, privacy, and participatory data governance. It developed open-source tools and ran real-world pilots in the city (in digital democracy, citizen science, and data commons). The city aimed to treat data as public infrastructure and empower residents to actively manage their data privacy and sharing preferences. Pilots included environmental sensor networks and platforms for anonymous, consent-based data sharing. https://ajuntament.barcelona.cat/digital/en/technology-accessible-everyone/accessible-and-participatory/decode

Vandana Shiva. Biopiracy: The Plunder of Nature and Knowledge first published in 1997 by South End Press. Again in 2016 by Penguin Random House. It’s not about the Internet of Bodies or biometrics in particular but Dr. Shiva raises many concerns about genetic data from third world countries - specifically their theft by corporations and Western nations in the context of world politics - that’s outside the scope of this essay but connected to issues of biopower.

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot published in 2010 was also made it into a movie in 2017. They tell the story of the HeLa cells, which were taken from Henrietta Lacks, an African American woman, without her consent in 1951 and were widely used in scientific research and commercial applications. Ownership of the HeLa cell line has never belonged to Henrietta Lacks or her family; instead, the cells became "general scientific property" and were used without compensation to her descendants. The case is widely recognized as a precursor to modern ethical debates about bodily autonomy, consent, and the commercialization of human biological materials—issues that are central to contemporary "Internet of Bodies" (IoB) discussions, where personal biological data is collected and potentially exploited. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/henrietta-lacks/immortal-life-of-henrietta-lacks